Ignaz Semmelweis was a Hungarian physician working at Vienna General Hospital's First Obstetrical Clinic in the mid-19th century. At that time, puerperal fever, also known as childbed fever, was a major cause of death among women who had just given birth. It was noted that the death rate in the clinic where medical students were trained was significantly higher than that in the second clinic where midwives were trained. This puzzled Semmelweis.

During his tenure at the clinic, a tragic event occurred. A friend of his, Jakob Kolletschka, who was a pathologist, died after accidentally being poked with a student's scalpel during an autopsy. Kolletschka's symptoms before death were similar to those of the women dying from childbed fever.

This incident sparked an insight. Semmelweis hypothesized that there was some "cadaverous material" from the dissected bodies that was being transferred to the women during childbirth. The medical students often went directly from autopsies to examine women in labor, whereas the midwives in the Second Clinic were unknowingly practicing safer procedures simply because they weren't conducting autopsies and then attending to childbirth, unlike the doctors and medical students in the First Clinic.

To test his theory, he instituted a policy requiring medical staff to wash their hands and instruments in a solution of chlorinated lime, a substance known to remove the putrid smell associated with the cadavers.

The results were dramatic. The mortality rate in the first clinic fell from 18.27% in April 1847 to 2.27% in June 1847, just two months after implementing the hand-washing policy.

Despite this clear empirical evidence, Semmelweis's idea was widely rejected by the medical community because it cannot be explained with science then. His theory did not fit with the dominant miasma theory of disease, which asserted that diseases were caused by bad air, not tiny particles transferred from person to person. Unfortunately, the rejection from his peers and the stress it caused led to a serious decline in Semmelweis's mental health. He was committed to an asylum in 1865, where he died at the age of 47.

- Scientific Explanation(inference): This is an explanation that uses scientific concepts, theories, or models to explain a particular phenomenon. It usually involves the application of the scientific method, which includes hypothesis formulation, experimentation, data collection, and analysis. A scientific explanation should be logical, consistent with existing scientific knowledge, and, crucially, open to falsification (the potential for a hypothesis to be proven wrong).

- Clinical Evidence: This refers to the data that healthcare practitioners use to make decisions about the care of individual patients. This evidence is usually derived from scientific research, particularly clinical trials, observational studies, and systematic reviews of the existing scientific literature. Clinical evidence focuses more on practical outcomes and effectiveness, often with less emphasis on the theoretical underpinnings.

From the perspective of scientific explanation, Dr. Semmelweis's recommendation lacked a solid theoretical basis at that time. The dominant miasma theory of disease believed diseases were caused by "bad air," and the concept of microscopic germs causing infections was not yet accepted. So, when Dr. Semmelweis insisted that doctors wash their hands, his peers didn't understand why this would make a difference. They could not relate it to any existing scientific theory or model of disease.

However, from a clinical evidence perspective, Dr. Semmelweis had a strong case. His observational studies showed that the practice of hand-washing led to a decrease in the mortality rate from childbed fever. He had the empirical numbers, the raw data, to demonstrate the effectiveness of his intervention. The doctors could see this evidence but chose to ignore it, primarily because it didn't fit with their existing scientific understanding.

This example nicely illustrates the tension that can sometimes exist between scientific explanation and clinical evidence. While scientific explanations provide the theoretical frameworks that help us understand and predict phenomena, clinical evidence often deals with the realities on the ground, which might not always neatly fit into those frameworks. The best approach to healthcare incorporates both, using scientific explanations to guide the search for effective treatments, and clinical evidence to test and refine these treatments.

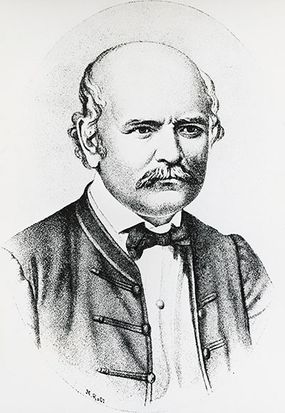

Regrettably, what purpose does it serve to construct a hospital bearing his name or issue the post-stamp with his portraits, following his tragic demise!